The largest animal on the planet doesn’t have teeth. In fact, blue whales belong to a unique group of mammals that eat their food in a very different way.

The humpback whale is part of the suborder Mysticeti. Members of this suborder use their baleen plates to filter out their food. © Amy Lutz/ Shutterstock

Cetacea is a group of mammals that contains whales, dolphins and porpoises. It’s divided into two smaller groups – baleen whales, also known as mysticetes, and toothed whales, also known as odontocetes. While toothed whales are generally highly social, baleen whales opt for a more solitary lifestyle, choosing to live in smaller groups.

Toothed whales, such as sperm whales, beaked whales, dolphins and porpoises, catch and eat their food using a variety of different forms of teeth.

Baleen whales include the bowhead whale, the humpback whale, the grey whale and, of course, the blue whale. These whales eat their food using a clever system called filter feeding.

What is filter feeding?

Baleen whales have a special structure in their mouth that enables them to filter feed.

Instead of teeth, they have baleen plates that hang down from their upper jaw. These are made from keratin – the same protein substance that our nails and hair are composed of.

Baleen whales use their baleen plates as a sieve. They take in huge mouthfuls of water and food and then push the water out through the plates, leaving only the food behind in their mouth.

Different species of baleen whale have evolved their own special styles of filter feeding over time.

The bowhead whale, for example, often swims along with its mouth open on the surface of the ocean, allowing the water to flow through its baleen plates while trapping prey inside. This species has the largest mouth of any animal, with baleen plates that can be almost four metres long.

Other baleen whales, such as the blue whale, identify large swarms of krill and engulf them in one huge gulp. They then contract their throat pleats and use their tongue to push the water out through their baleen plates, leaving only their prey behind.

“It’s remarkable and actually one of the most unusual feeding methods that any vertebrate has developed. It’s really complex, but also very fascinating,” says Richard Sabin, our Principal Curator of Mammals.

Filter feeding is a technique that needs to be carefully mastered. “It’s an incredibly energy-efficient mechanism, but they have to get it right,” says Richard. “Like any hunter, you want to be receiving more energy from the prey you capture than you’re expending in the hunt. So generally, baleen whales will take their time to assess the situation before committing.”

There are around 90 species of cetaceans living around the world. However, baleen whales account for a relatively small number of them, with only 15 known species.

Instead of teeth, baleen hangs down from the upper jaw of the whale’s mouth. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

The evolution of filter feeding

The ancestors of cetaceans used to live on land until around 50 million years ago when they began to move back into the oceans.

Researchers believe that baleen whales developed their clever filter-feeding method in response to increases in ocean productivity – the amount of biomass being produced through photosynthesis by marine plants and other organisms.

Baleen is keratin based, which means it doesn’t fossilise well, making it difficult to determine when and how it evolved. The oldest fossils of true baleen are around 15 million years old but baleen-related skull modifications have been found much earlier.

Some baleen whale fossils show the presence of both teeth and baleen, which indicates a gradual transition in their filter-feeding system. Further evidence of this can be seen during foetal development, with studies suggesting that baleen whale embryos initially develop teeth that are then reabsorbed before birth.

The evolution of baleen in whales has enabled them to feed in a way that’s effective and energy efficient, which has served them well as hunters. Most baleen whales, such as blue whales, feed on tiny shrimp-like crustaceans called krill. By filter feeding, they can consume huge amounts of this abundant food source quickly and efficiently, which has enabled them to grow to be some of the largest animals to have ever existed.

Blue whales feed on krill – a shrimp-like crustacean. © Tarpan/ Shutterstock

Baleen can tell us a lot about a whale’s life

Much like our hair and nails, baleen grows continuously, meaning that it stores an abundance of vital information.

“If we think about our fingernails, the bit closest to the finger is the newer growth so that’s going to give information on what you were doing and what you were eating about a week ago, whereas the tips of your nails are going to give you information on what you were eating longer ago,” Dr Natalie Cooper, our Principal Researcher, explains.

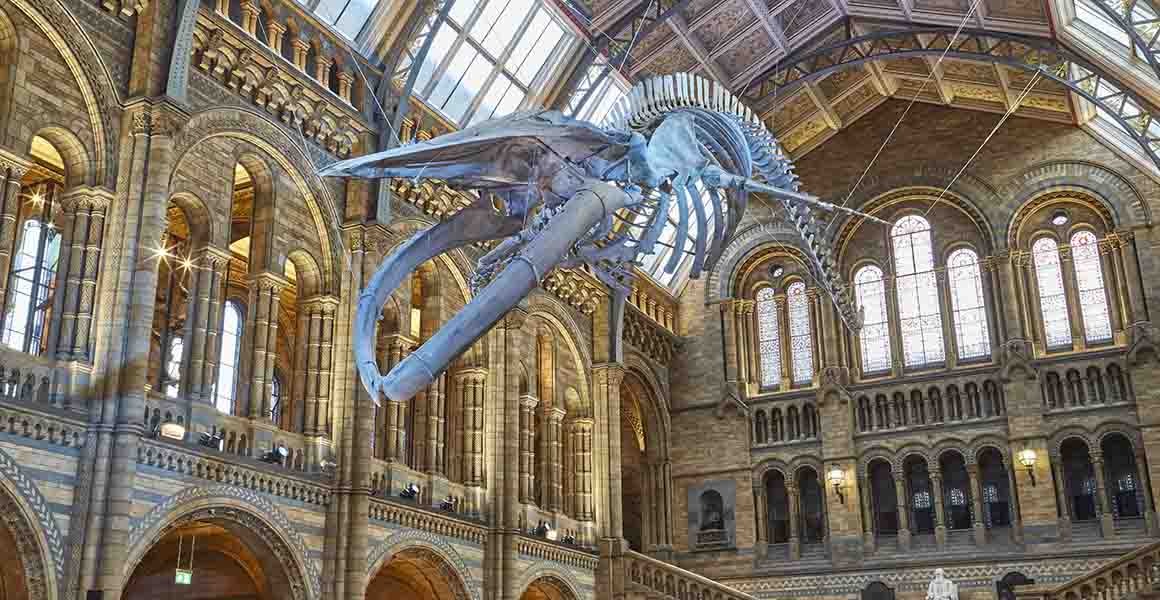

The same can be said about baleen. Hope, the blue whale skeleton on display in our Hintze Hall, is a perfect example of what we can learn from it.

Discovered in 1891 stranded on a sandbank just outside of Wexford Harbour in Ireland, Hope’s skeleton was purchased by us. Studies of this specimen’s baleen have revealed some incredible insights into its life.

“Baleen is an incredibly useful part of the animal to study, as it records so much information about their life,” says Richard. “When it arrived here in London in 1892, we could never have known just how useful it would be to science today.”

Hope’s baleen has taught us a lot about her life. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

From Hope’s baleen, we’ve been able to study the last seven years of her life. In the wild, blue whales can live to be around 80 years old, but Hope was quite young when she died – only about 15 to 20 years old.

Her baleen stored a record of her feeding habits. Much like blue whales in the northern hemisphere today, we can see Hope swam north towards Greenland and Iceland in the summer months to feed on the large amounts of krill there. Then she moved south towards the west coast of Africa in the winter.

Interestingly, it was discovered that in the last two years before she died, Hope travelled to the region around Cape Verde – where blue whales typically go to give birth.

From this finding, along with elevated levels of pregnancy hormones found in her baleen, we believe that Hope gave birth before she died.

Past and present threats to baleen whales

Whales were once widely hunted for their oil and meat. Baleen was a byproduct of the whaling industry. It was known as whalebone and was used, among other things, to make boning for corsets and hoop skirts.

Although hunting whales has been largely banned for several decades, they still face many threats. For example, recently, there’s been a significant increase in human-made noise in our oceans and seas.

“There’s a lot more stuff in the oceans now, so a lot more ships, a lot more wires, a lot more submarines and a lot more noise pollution,” says Natalie.

Busier waters mean there’s an increased risk of ships colliding with whales. © Eden Zang/ Shutterstock

When it’s time to mate, baleen whales call out to each other across the ocean for hundreds or even thousands of kilometres. The increase of noise in the oceans is making it harder for whales to find each other, and a mate.

“There’s been talk about trying to produce quiet areas of the sea. When we get whales swimming up the River Thames, for example, we think it’s probably because they’ve been confused by underwater noise and just panicked and ended up in the wrong place,” says Natalie.

Some baleen whale species, such as the humpback whale and the minke whale, have recovered their numbers in some areas since widespread whaling ended. However, others are struggling, mainly due to human-made issues.

For example, the Critically Endangered North Atlantic right whale, another baleen whale species, is increasingly involved in ship strikes. This is where ships collide with whales causing serious injury or death.

“North Atlantic right whales migrate in the same place where there’s really busy shipping lanes in the North Atlantic, and they’re being struck by ships all the time, which is really sad. They also get entangled in fishing gear.” says Natalie.

Learning for the future

Baleen not only serves as a clever, efficient feeding mechanism, it’s also a vital source of knowledge. The collection we care for includes specimens of baleen from 12 of the 15 baleen whale species. These specimens mean we can continue learning about the incredible lives of these creatures.

“I think it’s a lovely example of why museums and collections are important because we have all this material that we can do all this incredible research with,” says Natalie.

Discover Oceans

Find out more about why we are working to protect the oceans.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media