How gay is nature, really? In this exclusive excerpt of his book, A Little Gay Natural History, Josh Davis shines a light on the diversity of sex and sexual behaviour that’s always been observable in nature, for those who have been willing to look…

Common bottlenose dolphins, male and female, have been extensively studied engaging in same-sex sexual activity. Historically, this behaviour has been ‘explained away’ as something else. © cha_cha/ Shutterstock

The planet on which we live is filled with an extraordinary range of animals, plants and fungi. Collectively, they exhibit an astonishing diversity when it comes to what they look like, where they live and how they behave. And nowhere is this truer than when it comes to their sex and sexual behaviours.

Just how common are gay behaviours in nature?

It’s often quoted that around 1,500 species of animals show some form of homosexual behaviour. This includes animals from right across the tree of life: Hawaiian orb weaver spiders and common slipper shells, house flies, nematode worms and Humbolt squid, wood turtles, blackstripe topminnows, Guianan cock of-the-rocks and brown bears.

But this figure is likely a massive underestimate. Considering these behaviours are found in almost every branch of the evolutionary tree, it seems highly unlikely that they are limited to just a few hundred species out of some 2.13 million named to date. The most obvious assumption is that most species of animal probably exhibit some form of queer behaviour, and being a purely heterosexual species is the exception.

In some populations of giraffes studied, over 94% of all sexual activity observed was homosexual. © Vladimir Turkenich/ Shutterstock

How much do we understand about sexuality?

Despite the likely commonplace nature of non-heterosexual behaviour, for most of the history of science it has been covered up, ignored or disparaged. For a long time, it was generally assumed that animals only have sex to reproduce, and therefore homosexual behaviour was an evolutionary ‘paradox’. But it is now known that sex is a complex behaviour that can – and does – have multiple causes and outcomes, from stress relief, cementing bonds to just pure pleasure.

My book is not a justification for queer behaviours – animal or otherwise – as these behaviours need no justification. It is not a comprehensive list of queer behaviours or identities, and it is not making analogies between what is seen in nature and the human race.

My aim with A Little Gay Natural History is simply to give an overview of the sheer diversity of non-heteronormative biology and behaviours that exists in the natural world – those that are not based on the assumed binary of males and females taking on the ‘traditional’ roles that have historically been presented. Two of those examples are presented here.

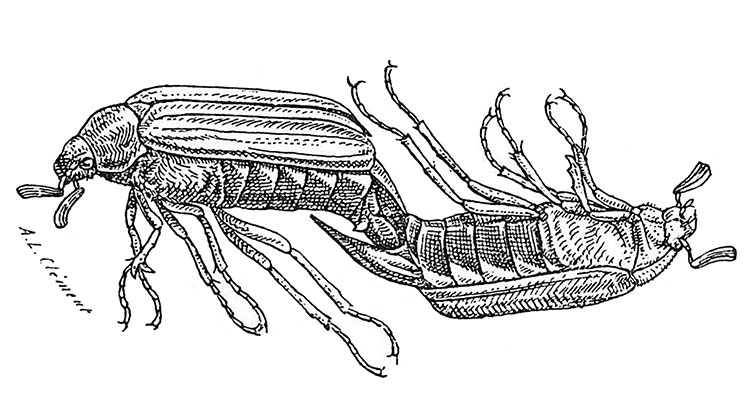

During the 1800s the topic of same-sex pairings among cockchafers enabled entomologists to start questioning why animals have gay sex. © nechaevkon/ Shutterstock

Cockchafers: The earliest depiction of homosexual sex in the animal kingdom

Cockchafers, also known as maybugs or doodlebugs, are a group of three species of beetle in the genus Melolontha. Found throughout much of central Europe, they have a long history and deep cultural connection with the region, primarily as a once significant agricultural pest. During the second half of the nineteenth century, they were also the focus of intense scientific debate about the nature of homosexuality.

This started in 1834, when the German school teacher August Kelch described his discovery of a larger common cockchafer having sex with a smaller forest cockchafer. What was unusual about this partnering, apart from the fact that it was cross-species, was that both beetles appeared to be male.

It is surprisingly easy to tell the difference between male and female maybugs – males have much larger, fluffier antenna. Despite this, Kelch initially thought that it couldn’t be two male beetles and was more likely a pairing between a male and a female with male antenna, perhaps in a similar way to how some female hens and pheasants have been known to develop male plumage.

But upon dissection he discovered the truth – these were indeed two male cockchafer beetles. One of the males used its ‘penis’, known as the ‘aedeagus’, to penetrate the other through its reproductive opening, pushing the receiving male’s aedeagus back into its body cavity. If the antenna hadn’t given things away, the act looked like two heterosexual beetles mating.

Explaining the gay away

Kelch and his colleagues tried to rationalize what they were seeing, writing “thus it was clear that Melolontha [melonlontha], as the larger and stronger of the two, had forced itself on the smaller and weaker male forest cockchafer, had exhausted it and only because of this dominance had conquered it, so to speak”.

This initial notion – that despite the tell-tale antenna, the penetrated individual must have been a female – was echoed again and again over the years as more reports of queer cockchafers surfaced. And as each of these examples also turned out to be homosexual pairings, researchers frequently fell back on the idea that, somehow, the beetle penetrating must have coerced the other into sex.

Fast forward 45 years and, in 1879, the Russian diplomat and entomologist Carl Robert Osten-Sacken described his own observations of male–male maybug pairings. But this time he questioned the assumption that the sex was somehow ‘forced’ by a dominant penetrating partner.

Osten-Sacken noted that the complexity of the coupling meant that what he would call the ‘passive’ beetle was clearly willing. He backed this assertion up with the fact that, in a number of cases, the ‘passive’ beetle was also the larger of the two insects. He argued that if it was all about dominance and strength, how come the smaller beetles were overpowering the bigger ones?

Osten-Sacken carefully stopped short of debating the morality of what he was observing, finishing with the somewhat understated line: “The interesting philosophical considerations which arise from such abnormal phenomena, I leave to the reader himself to address.”

This image of two male cockchafers having sex published in 1896 is thought to be the first ever image of non-human homosexual behaviour. Courtesy of the Smithsonian.

Necessity and preference

Things took another step forward in 1896 when the French entomologist Henri Gadeau de Kerville delivered a talk at the Société Entomologique de France conference about the ‘sexual perversion’ of male beetles. He built on Osten-Sacken’s remarks and made the argument that homosexual behaviour observed between male cockchafer beetles came in two forms: necessity and preference.

Gadeau de Kerville posited that male beetles kept together would likely have sex out of necessity, but that there was also clear evidence that, even in mixed environments, some males still chose to mate with each other.

He even went so far as to say that this behaviour “also took place among the higher vertebrates“, almost certainly a loosely coded reference to humans. This was an incredibly controversial statement to make at the time and was met with fierce resistance.

But Gadeau de Kerville didn’t back down. He published a long rebuttal in response to this backlash, doubling down on his assertions. In the process he produced an extraordinary drawing of two male cockchafer beetles having sex, thought to be the first ever image of non-human homosexual behaviour.

Marginalising the evidence

While de Kerville never went so far as to support homosexuality, he was still widely denounced and, on through the 1900s, reports of queer behaviour amongst beetles ebbed away, with those that did appear mainly being published in obscure publications.

The debate illustrates how established scientists continued to categorise queer behaviour in animals as ‘unnatural’ or ‘abnormal’.

Despite more and more examples of such behaviour in nature being reported, the legal, social and theological resistance of a society determined to keep the status quo alive held fast, even if it meant twisting and warping observations in order to explain the gay away.

Lesbian gull pairings and moral outrage

In 1972, well over a century after Kelch described his observation of gay sex in cockchafers, a pair of researchers set off to study the gulls nesting on Santa Barbara Island, off the southern coast of California.

It is difficult to tell male and female western gulls (Larus occidentalis) apart, but while studying the birds one of the researchers noticed something curious: some of the couples were sitting on an unusually high number of eggs.

Typically, the gulls lay between two and three eggs per nest. But some were incubating up to six or seven eggs, in what the biologists called a ‘supernormal clutch’. They concluded that these nests were tended by two female birds that had formed a lesbian pairing, courted, laid eggs and raised young together.

Studying the colony of western gulls for three years, they found that out of the 1,200 gull pairs studied, up to 14% were same-sex. Some of the eggs were fertile, suggesting around 15% of the female gulls were consorting with males at some point before returning to their female partner.

The research on ‘lesbian’ gulls came at a time when queer communities across the USA were organising themselves and challenging the status quo. © Gerald A DeBoer/ Shutterstock

Dynamite in a tinderbox

By 1977 the scientists were eventually ready to publish their findings, but they couldn’t have predicted the political fallout that resulted.

The research dropped right into the middle of the gay liberation movement in the USA. A decade after the Stonewall riots, queer communities across the country were organizing themselves and confronting the oppression they were experiencing.

In the same year that the gull paper was published, gay politician Harvey Milk was elected as city supervisor of San Francisco. At this time there was very little public awareness of queer behaviour in animals, and one of the prevailing arguments against homosexuality was that it was ‘unnatural’ and so ‘against God’s will’. The lesbian gull research, at that moment in time, was dynamite.

The research sparked countless newspaper articles and satirical cartoons. One headline ran “Your tax $$ wasted to study gay gulls”, while a group out of New York published a statement claiming that “100% of the sea gulls in the five boroughs of New York City were heterosexual”, presumably trying to imply that the queer gulls were a Californian quirk.

It didn’t stop there. When the House of Representatives debated the National Science Foundation’s budget in 1978 (the NSF had partly funded the research), the gull research was referenced and the budget held up for 10 days.

Emerging recognition of sexual diversity in nature

Despite the protestations of the religious and conservative right, the scientists were not put off. The team received countless letters of support from gay men and lesbian women.

The study became something of a cultural touchstone, inspiring a song titled Lesbian Seagull, written by Tom Wilson Weinberg in 1979 and later covered by Engelbert Humperdinck.The discovery of lesbian pairings amongst the western gulls might have been the first time a large proportion of the American society came across queer behaviour in animals, thanks to the level of media and political attention it received.

In the wake of the western gull paper, there followed a slow but steady flow of reports in scientific literature of homosexuality in the natural world, including in many other species of seabirds.

Over the next few decades numerous papers discussed the queer behaviour of countless gull species, from black-legged kittiwakes to laughing gulls, as well as studies of several tern species, such as the roseate and Caspian terns that form same-sex couples. Lesbian pairings have also been found in Antarctic petrel and Cory’s shearwater, which represent the first known species of burrow-nesting seabirds to show queer behaviour.

Perhaps the most well-known same-sex pairings in the bird world are those of the albatrosses. One of the most studied is the Laysan albatross. Around 31% of Laysan albatross pairs on Oahu, Hawaii, are between two females, with one female sometimes mating with a male before going back to her same-sex partner to raise the chick.

Why this behaviour is seemingly so prevalent in seabirds is not known. It could simply be that seabirds are a fairly well-studied group of birds, or it could relate to their colony nesting antics, which allow scientists to easily observe a large number of birds and keep track of relationships. Regardless, the story of the western gulls shows how science is inherently political insofar as it relates the natural world with human behaviour.

A Little Gay Natural History by Josh Davis, from which this article is an extract, is now on sale from our online shop.

A Little Gay Natural History is available to read now

The book is on sale now, including from our online shop.

I hope that the book and the examples it highlights flip the question of ‘why does homosexuality exist in nature when it appears to go against evolution?’ on its head. Instead, the majority of animals – and many of the plants – are out there right now, most likely engaging in plenty of queer activities without us even knowing.

Read the book

You can grab a copy of A Little Gay Natural History from our online shop

What on Earth?

Explore the wonderful diversity of the natural world.

Curious about the diversity of sex in nature?

Check out A Little Gay Natural History, our on-demand, online course, and see nature in a whole new light.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media