Birds-of-paradise can emit green, yellow and pale blue light from their bodies.

It’s believed this ability – known as biofluorescence – helps the birds to stand out or hide in their tropical forest habitats.

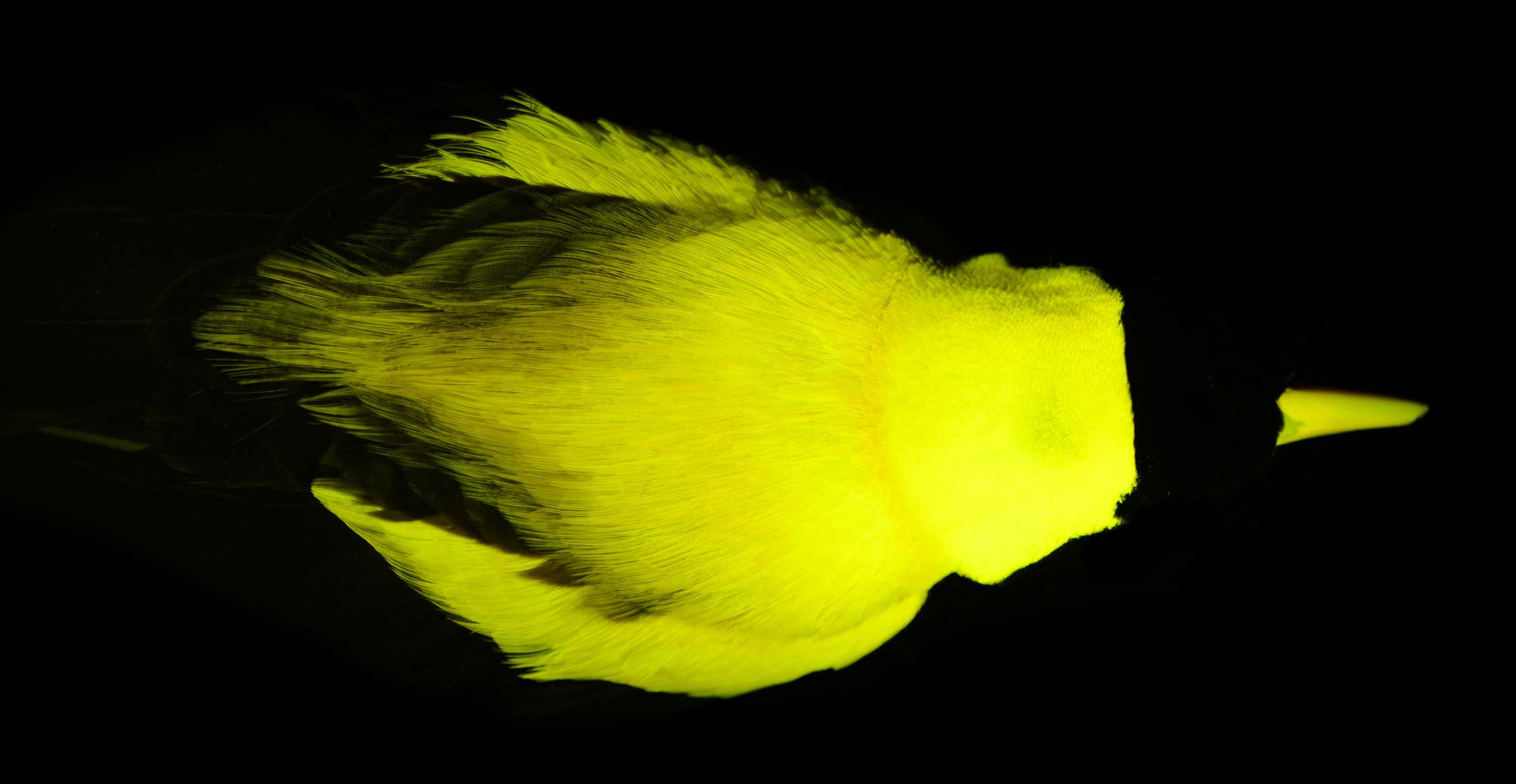

The feathers and beak of the red bird-of-paradise absorb blue and UV light and emit it in greens and yellows. © Rene Martin

Birds-of-paradise can emit green, yellow and pale blue light from their bodies.

It’s believed this ability – known as biofluorescence – helps the birds to stand out or hide in their tropical forest habitats.

For some of the world’s most decorative birds, the phrase ‘positively glowing’ has taken on a different meaning.

New research reveals that many birds-of-paradise emit light from special patches on their head, feet and even inside their mouths. Of the 45 species, 37 have been found to be biofluorescent, absorbing UV and blue light which they release in pale blues, greens and yellows.

The scientists, who published their findings in the journal Royal Society Open Science, believe that males use biofluorescence to enhance their courtship rituals. Male birds-of-paradise are already renowned for using bright colours, iridescent feathers and precise movements to catch the attention of potential mates, with biofluorescence heightening this spectacle even further.

The study was led by Dr Rene Martin, who carried out the research while based at the American Museum of Natural History.

“Birds-of-paradise are a charismatic group that has evolved numerous plumage traits that aid in signalling and reproduction,” says Rene. “They’ve evolved bright metallic-looking feathers that shine and reflect light due to structural coloration, while others have brightly pigmented feathers.”

“The breadth of patterns and behavioural displays across the group is astounding, so it makes total sense to find they have an additional element to their repertoire.”

While female birds-of-paradise don’t perform such dramatic displays as males, many still have biofluorescent patches. It’s been suggested that females might use the light to help them blend into the background instead, away from the gaze of any potential predators.

Even without its biofluorescence, the red bird-of-paradise’s bold colour scheme helps it to stand out in the forest. © Dicky Asmoro/ Shutterstock

Signalling isn’t just for cars and trains – it’s important for almost all life on Earth. Signals can be visual, chemical, electrical or otherwise, and are used to convey a variety of different meanings.

Some of the most important are used to try and attract a mate. It’s generally males who put on a show to try and woo females, but in birds like the jacanas it can be the other way around.

Male birds-of-paradise, however, are in a league of their own. To stand out among the darkness of the forest floor and the clustered tangle of leaves and branches, males put on dramatic performances to attract females who look on from nearby.

Male birds-of-paradise are renowned for their dramatic displays, with some species even performing upside down. © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

As they watch, female birds-of-paradise see far more of the display than we can. While humans see with three types of cone cell, birds have five. This means they can see beyond our visible spectrum, with some species able to see in ultraviolet (UV) light.

Oil droplets on the cones also help birds to better tell the difference between colours, enhancing their visual abilities further. Some birds also have UV filters in their eyes, which in fish are known to help detect biofluorescence.

Previous research has found biofluorescence in a few different birds, including penguins, parrots and puffins. While the reasons for these ‘glowing’ birds are relatively understudied, it’s believed their biofluorescent features might help for signalling and feeding young.

“I believe biofluorescence is likely a frequent occurrence across birds,” Rene adds. “While the study of biofluorescence in vertebrates is relatively new compared to that in invertebrates, we are now beginning to see an abundance of these studies.”

The plumage, skin and inside of the mouth can all be biofluorescent in birds-of-paradise. © Rene Martin

It’s thought that birds-of-paradise were biofluorescent for around a decade, based on preliminary research, but no further studies have been carried out since then.

Rather than using live birds, the team behind the current research turned to preserved bird specimens instead. This offered the opportunity to investigate birds-of-paradise without needing to travel to their habitat in Australia, Indonesia, and New Guinea.

“I believe natural history museums and their collections are extremely important for questions like this,” Rene says. “These institutions play a pivotal role in enabling scientists to perform research on hard-to-acquire, increasingly rare, threatened and endangered, or even extinct species.”

“Additionally, as technologies increase and change, historical specimens can be used for research in novel and innovative ways. Developments in imaging and lighting technology mean we are now able to better observe and measure biofluorescence across a variety of organisms, including birds.”

By moving blue lights over preserved birds-of-paradise in a dark room, the team were able to analyse the light the specimens emitted. They found that males from 21 species had biofluorescence on the outside of their body, while another 16 fluoresced with their mouth and throat.

Not all birds-of-paradise had these patches, however. Eight species from the genera Lycocorax, Manucodia and Phonygammus appear to have lost their ability to fluoresce, which may be due to differences in how they reproduce.

“Most core birds-of-paradise have multiple mates that they compete for in leks,” Rene explains. “These displays take a lot of energy to perform, and being brightly coloured can often lead to being predated upon more frequently than a more drab-coloured individual.”

“In contrast, these genera are believed to be monogamous. This mating system means males aren’t competing as much with each other for mates, so biofluorescence may have become more of a cost than a benefit for these birds.”

Now that biofluorescence has been revealed in birds-of-paradise, it’s up to future studies to show what other birds could also have it and how it might be used in the wild.

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media