According to English Heritage, Christmas pudding’s earliest variations can be traced back to at least the 1300s. Discover the stories behind the ingredients in modern recipes.

© Anna_Pustynnikova/ Shutterstock

The plants in your Christmas pudding

Emily Osterloff

From Christmas trees to sprigs of mistletoe, there are lots of plants we fill our homes with at Christmas, but what about those we eat?

Food has always been a big part of the festive season, none more so than the iconic figgy pudding. We take a look at the plants used to create this famous festive dish and the stories behind them.

Let’s tuck into the natural history of Christmas pudding!

Love it or hate it, Christmas pudding is a classic festive dessert here in the UK.

Whether it’s Delia’s, Nigella’s or Mary Berry’s, there are so many recipes out there, but there are some ingredients that pop up in almost all of them. For this article, we’ve gone with a traditional recipe created by Queen Victoria’s chief cook in the 1840s, Charles Elmé Francatelli. If it’s good enough for royalty, it’s good enough for us!

So, let’s dive into the store cupboard and break open the brandy as we look at the plants that make this pudding possible, from oranges and lemons to currants and cinnamon. If you’d like to make this Victorian version for yourself, check out the recipe on the English Heritage website.

Oranges and lemons

Oranges and lemons are seen as traditional Christmas ingredients, popping up in lots of recipes, including Christmas pudding.

© New Africa/ Shutterstock

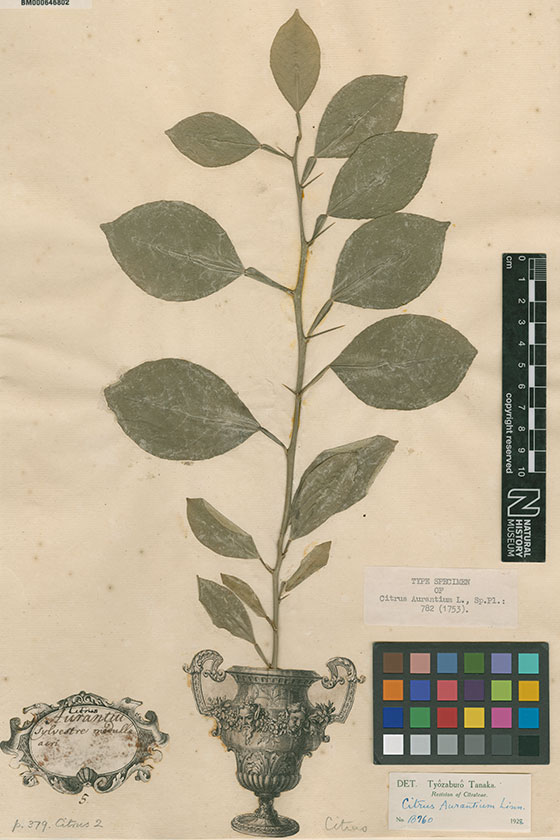

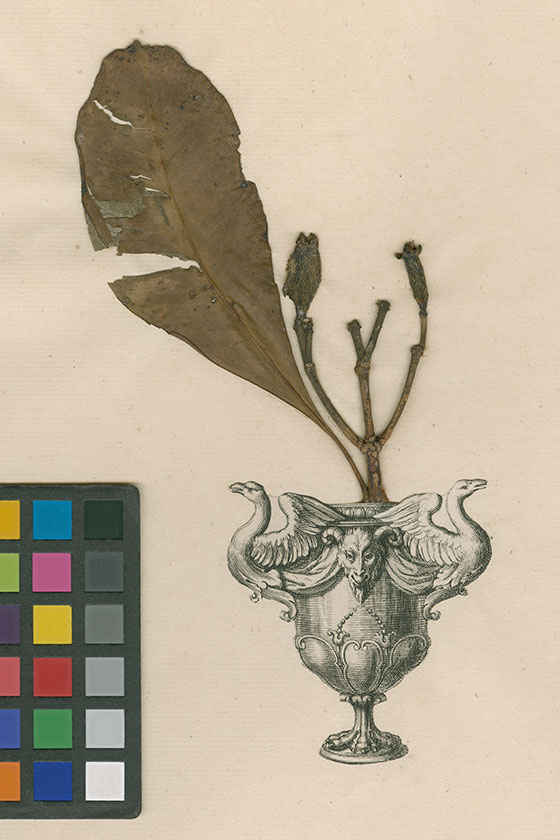

A bitter orange, Citrus x aurantium, specimen from the botany collections we care for.

Citrus fruits, mainly oranges and lemons, are used in Christmas pudding to give it a zesty kick. For centuries the orange remained the reserve of the rich. Today, however, they’re a staple in many households, but there’s more to these zesty, colourful fruits than you might think!

The sweet oranges in our supermarkets, Citrus × sinensis, are in fact a hybrid of pomelos, Citrus maxima, and the mandarin orange, Citrus reticulata. Lemons, Citrus × limon, are also a hybrid – in this case of citron, Citrus medica, and sour orange, Citrus × aurantium, which itself is a hybrid of pomelo and the mandarin orange.

Citrus fruits originated in southeast Asia in China’s Yunnan Province, Myanmar and northeastern India. The common ancestor of the citrus group probably lived about eight million years ago, but most of the citrus fruits you’ll see in the shops today were only cultivated in the last few thousand years. How modern citrus fruits are all related to each other is surprisingly complicated – they’re a tangled web of species, cultivars and hybrids.

Raisins, currants and brandy

Not only are raisins, currants and sultanas a main ingredient in Christmas pudding, they’re also an essential ingredient in another festive favourite – mince pies.

© Vanatchanan/ Shutterstock

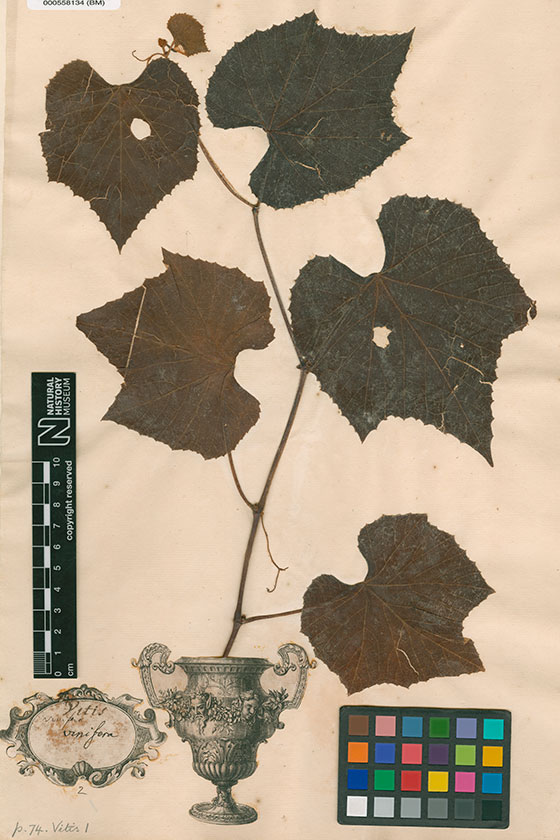

A common grape vine, Vitis vinifera, specimen from the botany collections we care for.

If you’ve ever picked up a Christmas pudding you might have noticed it’s a little weightier than other sponges – that’s thanks to all the raisins, sultanas and currants it’s packed with. Despite what their name might suggest these currants are not closely related to blackcurrants or redcurrants, they are in fact dried grapes. So too are raisins and sultanas.

Grapes are technically berries. Botanically speaking, a berry is a fleshy fruit produced by a single ovary of a flower. Despite their names, strawberries and raspberries aren’t berries. In fact, the crunchy bits on the outside of strawberries that we think of as seeds are all individual fruits called achenes.

So, currants aren’t currants and strawberries aren’t berries, but grapes are – confusing right!

Many recipes recommend soaking the raisins, currants and sultanas in brandy, which you guessed it – is also made from grapes! Brandy is distilled wine. You can make wine from other fruits, but grapes are the most commonly used, and winemakers have been using them for thousands of years. Who knew the Christmas pudding was so grape heavy!

Flour

Wheat is one of the oldest and most valuable crops in the world – it gives us flour, which is a fundamental ingredient in so many baking recipes.

© Mykola Mazuryk/ Shutterstock

A common wheat, Triticum aestivum, specimen from the botany collections we care for.

Flour has traditionally been the foundation of a lot of baking, so it’s no surprise that it pops up in the recipe for figgy pudding. We make flour from a whole variety of plants, including quinoa, chickpea and rice. But in UK supermarkets, wheat flour is the most common. According to the UK Flour Millers Trade Association, it’s in a third of all our grocery products.

Wheat, Triticum aestivum, is not only one of the world’s most valuable crops but also among one of the oldest. We’ve been farming it for around 10,000 years, and over time have developed bigger and stronger varieties, but there’s a problem.

A lot of modern wheat is genetically identical. This means it’s vulnerable to diseases and extremes of weather, from heatwaves to flooding. It would take just one disease that can’t be fought off or an increase in temperature that can’t be tolerated, for all our primary wheat crop to be wiped out, with major impacts on the global food supply.

Our scientists are using the collections we care for to study how wheat’s genome has changed over time. This will help us find and develop strains of wheat that are less reliant on fertilisers and pesticides and that can be grown in harsher climates. This is vital to making sure we can continue to feed the world in the future.

Sugar

Sugarcane is one of two plants that most of the sugar in our supermarkets is made from.

© Yatra4289/ Shutterstock

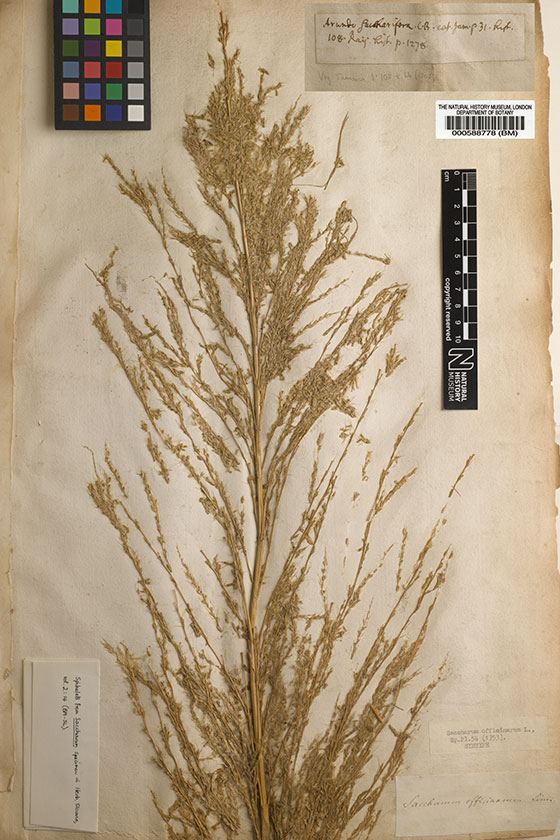

A sugarcane, Saccharum officinarum, specimen from the botany collections we care for. These are the spikelets from the top of a sugarcane plant.

Christmas pudding is the ultimate sweet treat to round off the festive feast, so it should come as no surprise that one of its main ingredients is sugar. We get sugar from sugarcane, Saccharum officinarum. If you’ve ever seen it growing, you’d be forgiven for mistaking it for bamboo – a fellow member of the grass family Poaceae. Sugarcane is typically grown in warmer climates, often on large plantations, which can have a negative impact on nature.

But there are alternatives. Would you believe us if we told you that in the UK we use a cultivar of the bright red vegetable beetroot, Beta vulgaris, to make sugar? In fact, most of the sugar that we grow in the UK comes from this cultivar called sugar beet, which has a white, sucrose-filled root.

We make lots of other sugars and sweeteners from plants too. The sugar substitute stevia is made from Stevia rebaudiana – a plant in the daisy family. Maple syrup is boiled sap from maple trees – mostly from the sugar maple species, Acer saccharum. Then there’s palm sugar, which is derived from various types of palm trees in the family Arecaceae. Not to mention agave syrup, which comes from juice extracted from agave plant cores, and many more besides.

Nutmeg

We get two store cupboard ingredients from Myristica fragrans fruit. Its seeds are the spice we know as nutmeg and mace is made from the seeds’ red coverings.

© Jamaan/ Shutterstock

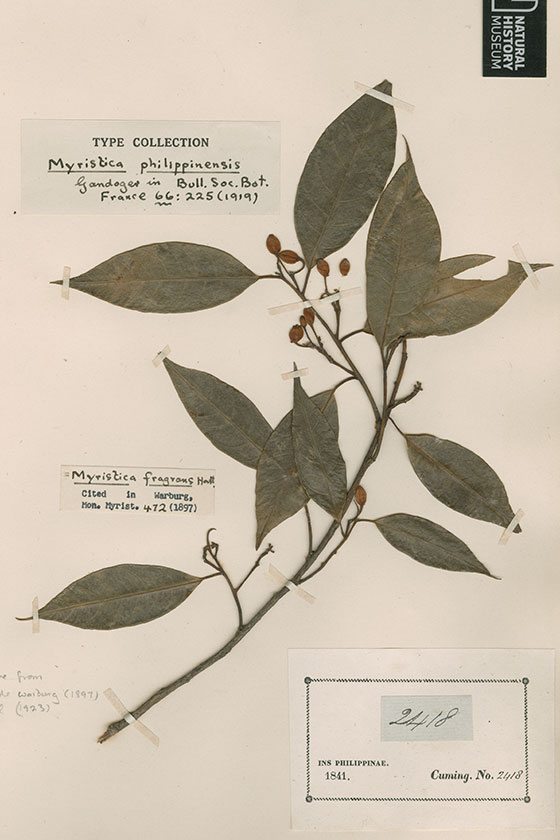

A nutmeg tree, Myristica fragrans, specimen from the botany collections we care for.

No Christmas pudding would be complete without the addition of a dash of nutmeg. We extract two spices from the nutmeg tree, Myristica fragrans. Its seeds become the whole and ground nutmeg you get in supermarkets, and we use the seeds’ bright red coverings to make the spice mace.

Nutmeg trees are grown in tropical locations around the world, but they’re originally from the Banda Islands, which are part of Indonesia’s Maluku Province.

For most people, nutmeg is safe to eat in small doses, but it’s not something you should eat in large quantities, as it can lead to nutmeg poisoning. A medical report from 2003 documents the case of a patient presenting with a variety of symptoms including heart palpitations, nausea and dizziness. It turned out they had added 50 grammes of nutmeg to a milkshake – that’s about the same as a whole regular jar of spice in a UK supermarket.

Cloves

Cloves are a classic Christmas spice, turning up in everything from mulled wine to bread pudding.

© Vunishka/ Shutterstock

A Syzygium aromaticum specimen from the botany collections we care for. We get cloves from the flower buds of this tree.

A sprinkling of cloves adds a little spice to your Christmas pudding. Ever wondered, though, why they’re such a strange shape? Well, cloves are actually flower buds from a tree called Syzygium aromaticum. When they’re ready to be harvested, these flowers are bright red, but become hard and turn deep brown when dried.

Like nutmeg and mace, cloves are originally from the Maluku Province in Indonesia. This archipelago was once known as the Spice Islands by European colonisers, who started arriving there in the sixteenth century. What followed was a prolonged period of conquest and killing as invading nations endeavoured to claim resources, including spices, which were much sought after in Europe.

Cinnamon

Nothing says Christmas like the smell of cinnamon, whether it’s from traditional German lebkuchen biscuits or yuletide-scented candles.

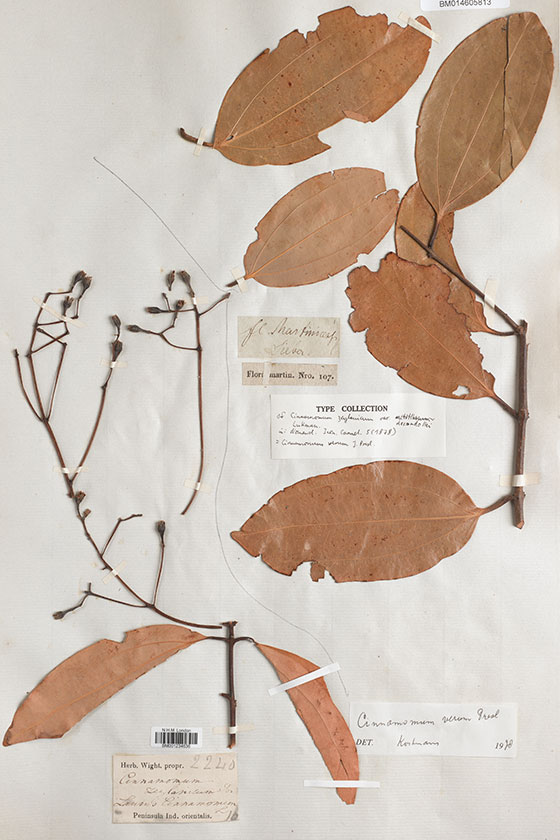

© BarbaraGoreckaPhotography/ Shutterstock

A true cinnamon tree, Cinnamomum verum, specimen from the botany collections we care for.

A pinch or two of cinnamon is essential in most recipes, adding festive flavour to the pudding. You’ll typically find two types of cinnamon in the shops – a finely ground powder and sticks. The woody nature of a cinnamon stick is a bit of a clue as to where this spice comes from – trees. Specifically, it’s the inner bark of Cinnamomum trees, of which there are around 250 species, though we don’t get cinnamon from all of them.

Perhaps one of the best known is the commercially valuable Cinnamomum verum, which is regarded by some as the gold standard when it comes to cinnamon. It’s originally from Sri Lanka and most of the world’s supply is still grown there. This species is commonly known as true cinnamon or Ceylon cinnamon – during British colonial rule Sri Lanka was known as Ceylon but was renamed in 1972.

Holly

Christmas puddings are often topped with a decorative sprig of festive foliage in the form of holly.

© Veronique Stone/ Shutterstock

A holly, Ilex aquifolium, specimen from the botany collections we care for.

No Christmas pudding is complete without a decorative sprig of holly on top. Holly, Ilex aquifolium, is a festive favourite with its bright green, leathery leaves and shiny, crimson berries. There’s some irony in it being added to make the pudding look more enticing, given that holly is actually toxic to us if we eat it.

But while you should avoid nibbling on this spiky plant, there are some animals that rely on it. Mistle thrushes, Turdus viscivorus, for example, are fond of holly’s bright red berries. In fact, these birds will fiercely defend holly trees to protect their food reserve.

Mistle thrushes like the berries from another plant we associate with Christmas too. They’re big fans of mistletoe, Viscum album, and this may be where their common name comes from.

Plants, like all nature, play such an important role not only in our survival, in terms of providing us with food, but in our cultures and traditions too. So, when you’re tucking into your Christmas pudding this year, spare a thought for all the amazing plants that go into making this delicious yuletide treat.

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media