The Dumbo octopus is an elusive cephalopod that gets its name from its large ear-like fins, which resemble those of the lovable Disney elephant.

But there's still lots we don't know about these mysterious creatures.

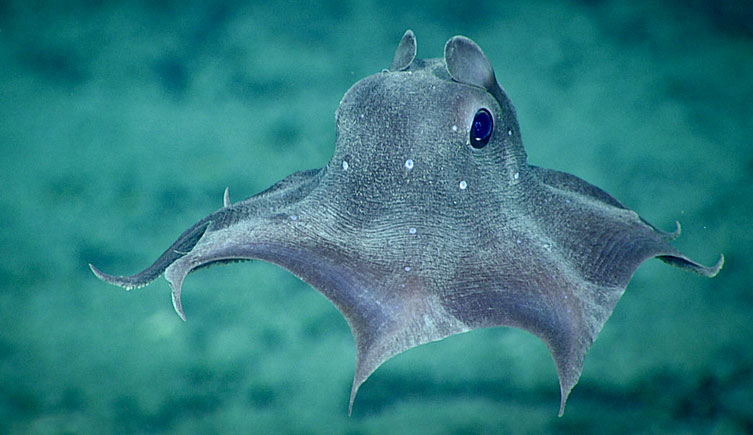

It's clear why the Dumbo octopus is often called the cutest octopus! © NOAA Ocean Exploration (CC BY-SA 2.0) via Flickr

The Dumbo octopus is an elusive cephalopod that gets its name from its large ear-like fins, which resemble those of the lovable Disney elephant.

But there's still lots we don't know about these mysterious creatures.

Dumbo octopuses are semi-translucent and have prominent fins on their bell-shaped bodies (also called a mantle). They have large eyes, but it's not known how good their eyesight is.

The octopuses also have a single line of about 65-68 suckers along each arm. These are flanked by hair-like projections called cirri. This places them in the deep-sea cirrate octopus group, which is one of the two main divisions of octopuses. The other division is the incirrate octopuses, which live in shallower waters and do not have cirri on their limbs.

'They look very different from other octopuses,' explains Jon Ablett, Senior Curator in Charge of Mollusca at the Museum. 'They're very blobby and gelatinous, which gives them an otherworldly alien-like look, especially when they're brought up to the surface.'

Dumbo octopuses are relatively small. They grow to an average length of 20-30 centimetres.

Some bigger specimens been found, however. The largest so far was 1.8 metres long and weighed 5.9 kilogrammes. But this is still tiny in comparison to the biggest cephalopod species, the colossal squid.

Dumbo octopuses live in the deep open ocean, at 1,000 to 7,000 metres below the surface. These depths are known as the bathyal zone (1,000-3,000 metres) and the abyssal zone (3,000-6,000 metres). No sunlight reaches these zones and the water is very cold.

The deepest confirmed sighting of a Dumbo octopus was made in 2020, when a one was spotted and captured on film almost 7,000 metres down in the Java Trench. This sighting suggests Dumbo octopuses could even live in the hadal zone, which is the deepest part of the ocean. It includes anywhere that is more than 7,000 metres below the surface.

It's possible different species of Dumbo octopus could occupy different depth ranges.

Dumbo octopuses are well-adapted to the high pressures and cold of the deep sea, and are not easy to collect for scientific study. Specimens often reach the surface in poor condition. © Darren Stevens (CC BY 3.0) via Wikimedia Commons

'Light can only penetrate to 1,000 metres,' says Jon.

'After 1,000 meters, the only light you find is produced by animals. So when you get down to near 7,000 meters, it's a completely different environment. It's pitch black, the pressure, the temperature - these are all things that would be completely unsurvivable to creatures that live at the top of the ocean.'

Dumbo octopuses may live worldwide in tropical to temperate latitudes.

Dumbo octopuses navigate the water by slowly flapping their ear-like fins, using their eight limbs to steer. Their mantle contains internal cartilage to help support their strong fins.

They are also neutrally buoyant. This allows them to passively drift through the water.

Dumbo octopuses belong to a group called umbrella octopuses (Opisthoteuthidae). The species in this group - including this Opisthoteuthis agassizii individual - all have deep webbing between their limbs, which makes them look like an umbrella opening and closing as they swim. © NOAA Ocean Exploration (CC BY-SA 2.0) via via Flickr

So far, 17 valid species of Dumbo octopus have been discovered, but there could be many more. Because these animals can live at such extreme depths, specimens are rare and often reach the surface in poor condition.

'When you don't have perfect specimens, it's hard to understand some of the features that we might use in classification,' explains Jon.

'It's sometimes hard to know whether you're seeing variation within a species or two different species.'

'We don't think they are particularly agile predators, so they're going to be scraping up whatever they can find,' says Jon.

The dumbo octopus is thought to use the hair-like cirri on its arms to waft food towards its mouth.

This limits what the Dumbo octopus can eat, with them only consuming organisms up to 1-2 millimetres in size. This likely includes molluscs, small crustaceans such as copepods, amphipods and isopods, bivalves such as oysters, snails and bristle worms.

This is a Cirroteuthis specimen. These octopuses have also been given the nickname 'Dumbo' as they also have large fins, however they are in a different family to the Dumbo octopuses in the genus Grimpoteuthis.

In the shallower parts of their depth range, some of the predators of dumbo octopuses include deep-diving fish such as tuna and some sharks, and mammals such as dolphins.

But in the deep ocean, there are relatively few predators.

This may be why Dumbo octopuses lack some of the defensive characteristics often seen in other cephalopods. They don't have an ink sac, so they can't defend themselves by squirting ink at predators. They may also lack the ability to move rapidly through the water by jet propulsion.

It has been estimated that a Dumbo octopus has a lifespan of 3-5 years.

Dumbo octopuses occupy a vast and rather lonely seascape. To maximise their chances of reproducing, they seem to have developed specialised behaviours.

'In the deep ocean, finding a mate is problematic and if you meet one, you probably want to be able to mate with them even if you're not quite in breeding condition,' explains Jon.

'Females seem to have eggs constantly at different stages of development. By having this 'conveyor belt' of eggs ready, they can mate and lay eggs whenever the opportunity arises.'

This differs from other cephalopods, which usually have one or two specific breeding seasons.

It is thought that the male Dumbo octopus stores sperm in a projection on one arm and when they encounter a female, they transfer the sperm over in a convenient sperm packet.

'Females may even be able to store sperm long-term, so even if they don't have any eggs ready, they can store it until they're ready to fertilise them.'

Female Dumbo octopuses lay their eggs on the seafloor, attached to rocks, coral or other hard surfaces. Young hatch from their eggs at a large size and are immediately capable of surviving on their own.

The Dumbo octopus was first discovered during the ground-breaking 1872-1876 Challenger expedition.

Their genus, Grimpoteuthis, wasn’t described until 1932, however.

Grimpoteuthis was named by Guy Robson, a former Zoology Department curator at the Museum. Two of the specimens discovered on the Challenger expedition and now classified as Dumbo octopuses are housed in the Mollusca collection.

We don't have enough information on the Dumbo octopus to know if they are endangered. But even though they live in the deepest reaches of our oceans, human activity could still negatively impact them.

'Every ecosystem is delicate, especially such specialised habitats like the Dumbo octopus lives in,' Jon explains.

'Deep-sea mining affects animals that live very close to the seabed like the Dumbo octopus. Microplastics have been found in some of the deepest parts of the ocean, and if the ocean gets more acidic, it could affect many small organisms' ability to form properly, or even effect their ability to form a shell.'

'It's important to minimize our impact on these habitats, so that we don't damage species or lose them entirely – before we even really knew them.'

A common fangtooth, a companion of the Dumbo octopus in the bathyal zone of the ocean, was recently found to have microplastics in its stomach. The fish had eaten a cock-eyed squid and a bearded sea devil, which had both eaten plastic, suggesting that plastic might be being passed up the food chain.

Heading to the beach this summer? Get involved in a little community science and help protect the Dumbo octopus by taking part in events such as the Big Microplastics Survey.

Want to dive deeper into the fascinating world of the octopus? Read eight more surprising facts about these mysterious creatures.

Find out more about why we need to protect oceans and read about the pioneering work of our marine scientists.

Just how weird can the natural world be?

Don't miss a thing

Receive email updates about our news, science, exhibitions, events, products, services and fundraising activities. We may occasionally include third-party content from our corporate partners and other museums. We will not share your personal details with these third parties. You must be over the age of 13. Privacy notice.

Follow us on social media